Pericarditis

Learn about pericarditis through its symptoms, treatments, preventative measures, anatomy and physiology, biological mechanisms behind pericarditis, and more.

HEART DISEASE

Avya Patel and Ritvik Sethi

4/17/20255 min read

Pericarditis

What is pericarditis?

Pericarditis is the inflammation of the pericardium, the double-layered, fluid-filled sac surrounding the heart.

While it only has a 1.1% death rate in developed countries, pairing of the condition with other health conditions (e.g. COVID-19, influenza, cancer) can significantly amplify the mortality rate.

There are several types of pericarditis, each with their own

causes and symptoms: acute, chronic, constrictive, infectious, idiopathic, traumatic, uremic, and malignant. Of these, the most important are addressed below.

Acute - sudden inflammation and onset of syndromes

Chronic - inflammation that lasts more than 3 months after the first acute attack

Constrictive - inflamed layers of the pericardium become stiff, thicken, and stick together, interrupts normal heart function and often caused by repeated acute attacks, most deadly variant

Idiopathic - any instance that has no known cause, makes up around 90% of all diagnosed cases

What causes pericarditis?

Pericarditis can be caused by infectious agents, most commonly viral pathogens such as Coxsackievirus B, Echovirus, Influenza, bacterial pathogens such as Streptococcus pyogenes, fungal, and parasitic infections. Non-infectious causes include autoimmune diseases, radiation, Post- Myocardial Infarction, and Drug-induced pericarditis.

Why is pericarditis harmful?

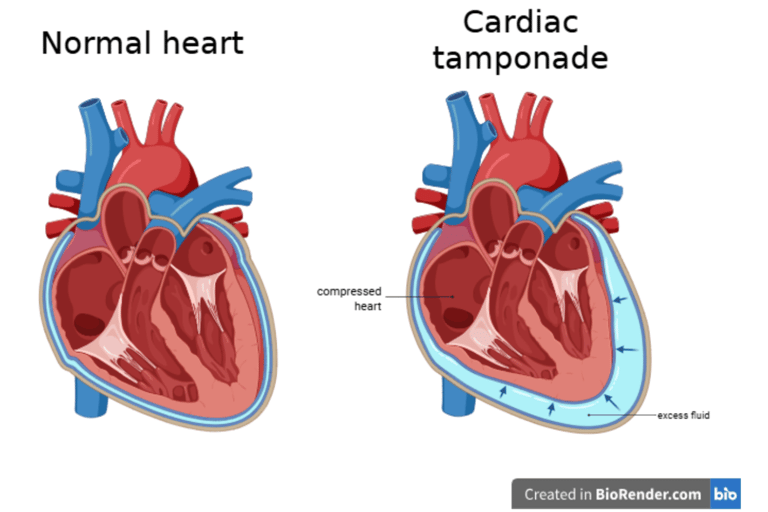

If untreated for a sufficiently long period of time, pericarditis can lead to pericardial effusion and eventually cardiac tamponade, a deadly complication.

Pericardial effusion refers to the buildup of fluid in the pericardium, between the two layers. When it occurs quickly, the pericardium doesn’t have enough time to stretch itself and accommodate the incoming fluid.

Normally, the fluid of the pericardium is a thin layer used to cushion the heart. But in the case of rapid pericardial effusion, the fluid occupies too much space, leaving the heart with little space to expand. This decreases the rate that blood is pumped through the heart, also known as the cardiac output, and reduces blood flow to the tissues of the body.

An extreme form of this is cardiac tamponade. This is when the heart has very little or no room at all to expand. Immediate treatment is required, because such a condition can make the heart stop, which can be fatal within minutes. See the image above for a visualization of this issue.

Another example of a complication rooted in pericardial effusion is cardiogenic shock, which occurs as a result of the heart pumping more and more rapidly to compensate for its reduced stroke volume, or amount of blood output per beat of the heart. At some point, once the heart can no longer keep up with the decreased stroke volume, the body enters cardiogenic shock, another condition that can be fatal if untreated.

A final significant issue following pericarditis is pericardial fibrosis, in which the thickened pericardium becomes fibrotic, forming excess fibrous connective tissue or scar tissue and interfering with expansion. This limits that heart’s ability to pump blood, similarly to pericardial effusion The mechanisms for this process are explained in the next section.

Biological mechanisms of pericarditis: cellular and molecular level

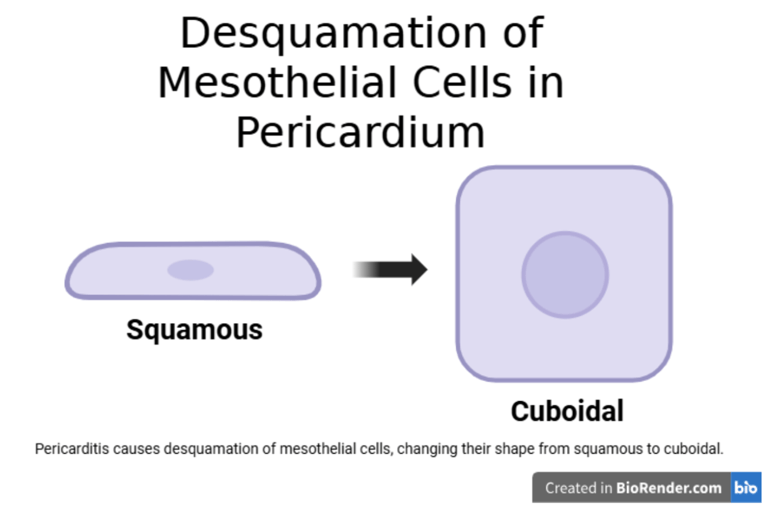

The mesothelial cells that line the heart are usually squamous, or flat, but pericarditis can cause desquamation of these cells. Desquamation in pericarditis changes the shape of these cells from the squamous shape to a boxy, or cuboidal, shape.

When this happens, these mesothelial cells are referred to as “activated.” The activated state of mesothelial cells have many functional differences as compared to the normal state.

Activated mesothelial cells secrete adhesion molecules and chemokines, which are a special type of cytokine, or signaling protein, that induce the movement of leukocytes, or white blood cells. In this case, both of these factors contribute to the inflammation of the pericardium. Moreover, activated mesothelial cells can contribute to pericardial fibrosis by producing extracellular matrix components.

Desquamation exposes the basement membrane and underlying connective tissue stimulate more inflammation. Additionally, it can cause fibrin deposition and adhesion formation between the visceral and parietal pericardium which gives the pericardium “bread and butter” appearance, suggestive of fibrinous pericarditis.

Finally, in pericarditis, the pericardial interstitial cells, which are the non-muscular cells in the pericardial space, play a role in extracellular matrix production and calcification of the tissue, which may cause it to harden.

Inflammatory cascade which leads to desquamation of mesothelial cells:

When the pericardium is inflamed, inflammatory cytokines such as L-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 are released. Additionally, neutrophils and macrophages migrate to the inflamed area, secreting reactive oxidative species (ROS) and proteases. These cytokines and molecules released by immune cells damage pericardial mesothelial cells by apoptosis, necrosis, and the loss of intercellular junctions.

This inflammation leads to cells detaching due to cytoskeletal breakdown and junctional disruption as mentioned above.

Prevention: steps to take to avoid getting the condition

Since pericarditis often occurs as a result of a previous viral, bacterial, fungal, or parasitic infection, it’s always beneficial to maintain good hygiene and stay up-to-date on vaccines.

Existing health concerns can also increase the risk of pericarditis, so keeping such conditions under control would benefit the chances of avoiding the disease.

Besides these, keeping in general good health with a balanced diet, regular exercise, and abstinence from smoking and drug abuse all play a key role in reducing the chance of contracting any disease.

Symptoms of pericarditis:

Main/ Common Symptoms:

Chest pain

Worsens when lying down (pericardial effusion)

Sharp, stabbing, or aching pain

Fever

Low or high-grade fever

Shortness of breath

Worsens when reclining or laying flat

Heart palpitations

Arrythmias, heart feels like it is fluttering, racing, or pounding

Fatigue or weakness

Cough

Swelling

In the legs, ankles, or abdomen (cardiac tamponade and/or pericardial effusion)

Less common symptoms:

Nausea and/or vomiting (normally due to severe pain)

Abdominal pain (right-sided heart strain or tamponade)

Pain that radiates to the jaw or arms

This is often misdiagnosed for a myocardial infarction.

Risk factors of pericarditis:

Infectious Causes:

Viral infections (most common)

Bacterial infections

Fungal/Parasitic infections:

Autoimmune/Inflammatory Diseases:

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

Scleroderma

Vasculitis syndromes

Post-cardiac injury factors:

Post-MI (Dressler’s Syndrome)- Autoimmune condition after a heart attack

Post-pericardiotomy syndrome- Post cardiac surgery

Metabolic/Other Causes:

Uremia (end-stage renal disease)

Hypothyroidism

Malignant cancers (lung or breast cancer, lymphoma, leukemia)

Complications of Pericarditis:

Pericardial Effusion: Can lead to a cardiac tamponade if too much fluid accumulation is present.

Cardiac output drops

Can be serous, fibrinous, purulent, or hemorrhagic

Constrictive Pericarditis: Leads to chronic inflammation due to fibrosis and calcification of pericardium.

Impaired diastolic filling, again lowering cardiac output, mimicking right heart failure.

Recurrent Pericarditis: Occurs in 15-30% of pericarditis patients, normally after incomplete treatment

Could also be autoimmune related.

Treatment options available once the disease is present

Often, mild cases of pericarditis subside on their own, without intervention. Otherwise, medications can be used during the healing process to ease symptoms.

First-line medications:

NSAIDs

Reduce inflammation and chest pain

Colchicine:

Reduces recurring pericarditis rate

Second-line medications:

Corticosteroids:

Often reserved for autoimmune pericarditis, patients who fail in NSAIDs or Colchicine.

Surgical options

Pericardiocentesis:

Emergency to remove excess fluid buildup due to cardiac tamponade

Pericardiectomy:

Surgical removal of pericardium, normally done for obstructive pericarditis or recurrent cases.